Character Strings-Datatypes

On 25/07/2024 by Robert CorvinoThere are four basic character string types in Oracle, namely, CHAR, VARCHAR2, NCHAR, and NVARCHAR2. All of the strings are stored in the same format in Oracle. On the database block, they will have a leading length field of 1–3 bytes followed by the data; when they are NULL, they will be represented as a single-byte value of 0xFF.

Note Trailing NULL columns consume 0 bytes of storage in Oracle. This means that if the last column in a table is NULL, Oracle stores nothing for it. If the last two columns are both NULL, there will be nothing stored for either of them. But if any column after a NULL column in position is not null, then Oracle will use the null flag, described in this section, to indicate the missing value.

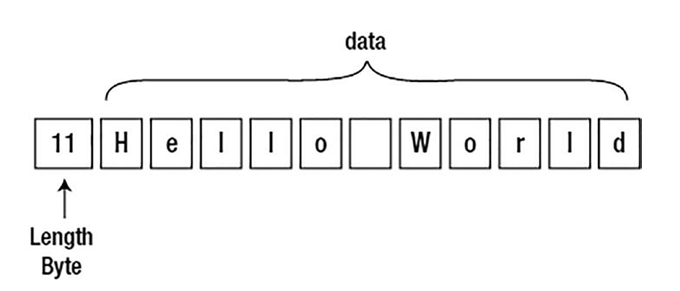

If the length of the string is less than or equal to 250 (0x01 to 0xFA), Oracle will use 1 byte for the length. All strings exceeding 250 bytes in length will have a flag byte of 0xFE followed by 2 bytes that represent the length. So, a VARCHAR2(80) holding the words Hello World might look like Figure 12-1 on a block.

Figure 12-1. Hello World stored in a VARCHAR2(80)

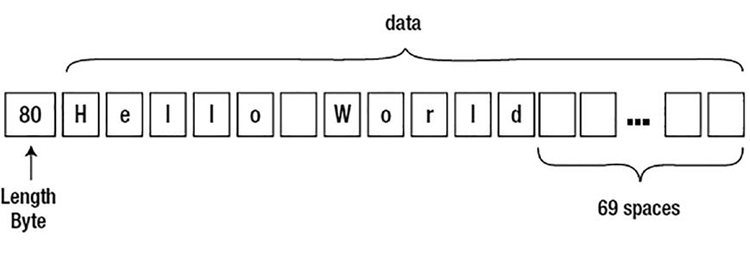

A CHAR(80) holding the same data, on the other hand, would look like Figure 12-2.

Figure 12-2. Hello World stored in a CHAR(80)

The fact that a CHAR/NCHAR is really nothing more than a VARCHAR2/NVARCHAR2 in disguise makes me of the opinion that there are really only two character string types to ever consider, namely, VARCHAR2 and NVARCHAR2. I have never found a use for the CHAR type in any application. Since a CHAR type always blank pads the resulting string out to a fixed width, we discover rapidly that it consumes maximum storage both in the table segment and any index segments. That would be bad enough, but there is another important reason to avoid CHAR/NCHAR types: they create confusion in applications that need to retrieve this information (many cannot “find” their data after storing it). The reason for this relates to the rules of character string comparison and the strictness with which they are performed. Let’s use the ‘Hello World’ string in a simple table to demonstrate:

$ sqlplus eoda/foo@PDB1

SQL> create table t (char_column char(20),varchar2_column varchar2(20));Table created.

So far, the columns look identical, but, in fact, some implicit conversion has taken place, and the CHAR(11) literal ‘Hello World’ has been promoted to a CHAR(20) and blank padded when compared to the CHAR column. This must have happened since Hello World……… is not the same as Hello World without the trailing spaces. We can confirm that these two strings are materially different:

SQL> select * from t where char_column = varchar2_column; no rows selected

They are not equal to each other. We would have to either blank pad out the VARCHAR2_COLUMN to be 20 bytes in length or trim the trailing blanks from the CHAR_COLUMN, as follows:

SQL> select * from t where trim(char_column) = varchar2_column;

CHAR_COLUMN VARCHAR2_COLUMN

Note There are many ways to blank pad the VARCHAR2_COLUMN, such as using the CAST() function.

The problem arises with applications that use variable-length strings when they bind inputs, with the resulting “no data found” that is sure to follow:

SQL> variable varchar2_bv varchar2(20) SQL> exec :varchar2_bv := ‘Hello World’; PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

SQL> select * from t where char_column = :varchar2_bv;no rows selected

So here, the search for the VARCHAR2 string worked, but the CHAR column did not. The VARCHAR2 bind variable will not be promoted to a CHAR(20) in the same way as a character string literal. At this point, many programmers form the opinion that “bind variables don’t work; we have to use literals.” That would be a very bad decision indeed. The solution is to bind using a CHAR type:

SQL> variable char_bv char(20)

SQL> exec :char_bv := ‘Hello World’;

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

However, if you mix and match VARCHAR2 and CHAR, you’ll be running into this issue constantly. Not only that, but the developer is now having to consider the field width in their applications. If the developer opts for the RPAD() trick to convert the bind variable into something that will be comparable to the CHAR field (it is preferable, of course,to pad out the bind variable, rather than TRIM the database column, as applying the function TRIM to the column could easily make it impossible to use existing indexes on that column), they would have to be concerned with column length changes over time. If the size of the field changes, then the application is impacted, as it must change its field width.

It is for these reasons—the fixed-width storage, which tends to make the tables and related indexes much larger than normal, coupled with the bind variable issue—that I avoid the CHAR type in all circumstances. I cannot even make an argument for it in the case of the one-character field, because in that case it is really of no material difference. The VARCHAR2(1) and CHAR(1) are identical in all aspects. There is no compelling reason to use the CHAR type in that case, and to avoid any confusion, I “just say no,” even for the CHAR(1) field.

Archives

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

Calendar

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||

Leave a Reply